A Brief History of Ad Fraud

Jonathan Marciano

|Marketing | September 08, 2020

Ad fraud has grown to be one of the easiest and most profitable enterprises for criminals. Despite several initiatives to limit the volume of ad fraud and click fraud on internet advertising, it continues to cost the industry billions each year.

In fact, current estimates put the total expected to be lost to ad fraud at $23 billion each year. And, all signs point to an annual growth of ad fraud.

So how did we get here? And why isn’t ad fraud under control yet?

Digital Advertising and the Birth of Ad Fraud

Sponsored posts and paid banner ads have been around since the early days of the internet.

To start with, most sponsored ads on the internet would have been in the form of banner ads, which were very obviously ads.

The very first banner ads were displayed on the website HotWired.com (now just known as Wired.com) in 1994, run by AT&T. These ads were incredibly effective, with a click-through rate of 44% – the sort of CTR that would knock down most modern marketers.

As you can see, it’s not even a particularly sophisticated ad. But with the internet still in its infancy and digital marketing still a futuristic concept, ads like this proved to be very effective.

These ads were often paid for upfront, with the ad above allegedly costing AT&T around $30,000. Later, banner ads would work on a CPM (cost per thousand impressions) basis.

Enter PPC

It was not until 1998 that pay-per-click (PPC) first appeared as an option for marketers. Goto.com was an upstart search engine powered by Inktomi, another popular search engine at the time. The owner of Goto.com came up with the ingenious idea of allowing businesses to pay to appear at the top of the search engine results for certain keywords.

And, they wouldn’t need to pay by impression; they would only pay if a site visitor clicked on their ad. At the time, this was revolutionary stuff. But we were still in the heyday of the whole dotcom boom, and most of today’s internet giants were still finding their feet.

In the mid to late 90s, search syndication was also starting to become a thing, and by extension, so were these paid ads. Sites like Yahoo! powered their search results from the most popular search engine of the day, Alta Vista.

Google was born in 1998 and quickly established itself as the superior search engine. Needing to monetize, Google spotted the potential in the Goto.com model and in offering their search and their paid results for syndication.

Early ad fraud: 1999

In this brave new world, the existence of ad fraud was felt pre-2000. In fact, a research paper released in 1999 found that there were already several relatively sophisticated forms of ad fraud being perpetuated online.

Ominously, the paper signed off by suggesting that these kinds of ad fraud attacks could undermine the viability of PPC; and also suggested that making this kind of behaviour auditable could continue to be a problem for web advertising.

For publishers to artificially inflate the clicks on their ads would have been, in 1999, pretty straightforward. And there was very little in the way of controls, or even awareness, around the threat of ad fraud.

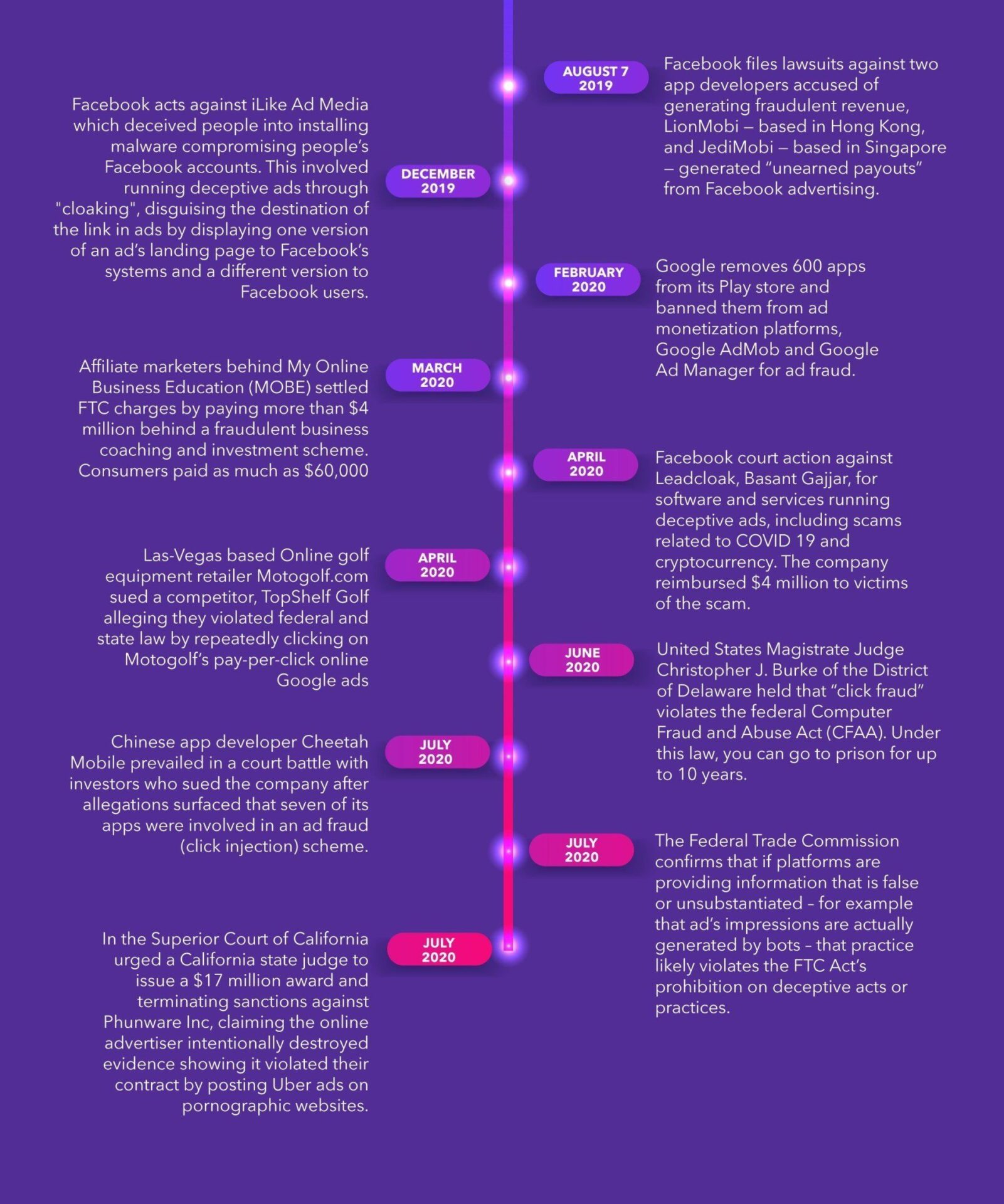

2006: click fraud challenges rage

Talk of click fraud continued to escalate and was a hot topic at search engine marketing conferences by 2006.

In January 2006, WIRED predicted that click fraud could swallow the internet. Both Yahoo and Google were sued in precedent-setting click fraud cases.

In 2006, Google published a 47-page report on its click fraud mitigation strategy, written by Dr. Alexander Tuzhilin, Professor of Information Systems at NYU. It stated: “The bottom-line conclusion of the report is that Google’s efforts against click fraud are, in fact, reasonable. At several points in his report, he calls out the quality of our inspection systems and notes their constant improvement. It is an independent report, so not surprisingly, there are other aspects of it with which we don’t fully agree. But overall, it is a validation of what we have said for some time about our work against invalid clicks.”

The company also appointed a “Click Czar”, Shuman Ghosemajumder, who worked at Google from 2003 to 2010. Speaking in 2019 about the challenge, he said: “We had just launched a product called Ad Sense [2003], that was the first time that many small blogs as well as large media companies, could monetize their websites. If you as a publisher could suddenly get a percentage of the revenue that was associated with your website, now you had a direct incentive to get as many clicks on those ads as possible. So, we started to see click fraud, in much more sophisticated ways than we had seen on Google.com. So we started investing in that area and needed to understand all the technical aspects of the problems – all of the signals we could collect from clients and the platform, but also how to be able to create the operational infrastructure within the company to be able to provide that capability to protect against attacks in as real-time fashion as possible. I ended up speaking to every corner of the company and external parties as well.”

2006-2017: Bots hit ad campaigns

However, the use of bots (known as a botnet) clearly started to become a problem across the internet. In a widely known stat, as business became digital-first, bots soon accounted for approximately 45% of all web traffic, and advertising campaigns were hit hard by sophisticated attempts to drain ad campaigns as money moved away from traditional advertising and to digital. Bots began to manifest themselves across all online advertising platforms and campaigns. Every year since, new bots have been found.

Early click bots would be pretty simple in their behavior, often powered by a few networked machines or servers. These click bots were also available to buy for anyone who wanted to use them.

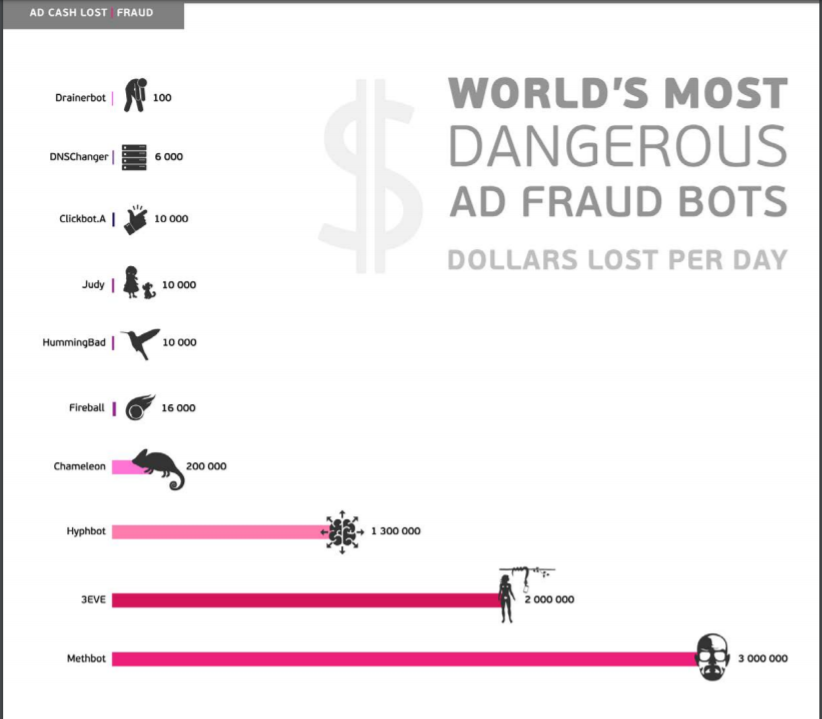

Bots such as i-Faker, FakeZilla, and ClickZilla could use anonymous proxies to create an illusion of being different users, although their activity was obviously automated. Some of the league of bots that hit the big time are below.

1) Methbot

With ad fraud becoming ever more sophisticated, it hit a high point with Methbot, easily the largest botnet campaign at the time. It’s thought that Methbot was active from at least 2015, with the campaign finally being taken down in 2017.

Methbot was run from at least 1,900 servers, which were used to generate IP addresses, spoof websites, and generate fake impressions using bots. The campaign was thought to be making around 300 million video impressions every day, with those impressions paying out an average of $13 per 1000 impressions.

It later transpired that the team behind Methbot was a gang of criminals who made around $7 million from ad fraud.

In fact, Methbot was just the dress rehearsal for what turned out to be an even bigger ad fraud botnet campaign.

2) 3ve

Pronounced ‘Eve’, the team behind Methbot switched modus operandi as Methbot was being dismantled by the FBI. 3ve was a similar, if uniquely different campaign using a network of malware bots as opposed to the data center technique used by Methbot.

With access to around 1.9 million infected computers and using bot clickers Miuref and Kovter to do its dirty work, 3ve was even more effective than its predecessor. It was also one of the first botnet ad fraud campaigns to game ads.txt, by creating composite URLs from outdated ads.txt lists.

3ve was later found to have generated over $29 million for the gang. Many of the fraudsters associated with 3ve and Methbot have since been arrested and convicted on counts ranging from wire fraud and money laundering to computer intrusion.

3) DrainerBot

The new generation of malware tends to focus on mobile devices. This makes the current generation of ad fraud malware capable of operating from within apps even if the device isn’t in use – a practice known as click injection or click spamming.

DrainerBot, discovered in 2019, was a mobile malware bot hidden in apps on the Google Play Store. Once downloaded, it was capable of clicking away on the background on hidden ads or watching videos.

In fact, by watching so many videos in the background, DrainerBot sapped users of their data allowances and also drained device batteries super-fast. Hence the name…

One study found that DrainerBot was capable of depleting batteries from 100% to 5% within an hour and used around 5GB of data in two weeks!

Calls for industry response to ad fraud

With more and more concrete and anecdotal data about the scale of click fraud, there followed plenty of industry wakeup calls. Initiatives to fight ad fraud encompassed the Trustworthy Accountability Group, the MRC, and the IAB, seeking to respond to the challenges. Unilever’s Keith Weed, responsible for the second-largest advertising budget in the world, prioritized the challenge of cleaning up advertising, including removing fraud. Weed put it bluntly in 2019: “We want to know that real people, not robots, are enjoying our ads – bots don’t eat a lot of Ben & Jerry’s. We will champion the good actors that help us in this while diminishing the roles of the bad.”

2019-2020: Sophistication and level of attacks increases

Nevertheless, the attacks against advertising campaigns show no signs of slowing down in 2020. By 2020, the ease of tools online to commit ad fraud and the appetite to drain digital advertising is unrelenting. Malicious SDKs for advanced and AI-powered click injection are sold in the Dark Web to the public for a fairly low price to perpetrate ad fraud, offering the opportunity, in the words of the suppliers to “emulate ad clicks and hijack clicks, including Google, Facebook and organic clicks.” Meanwhile data center-dwelling bots have been replaced by fraudsters using harderto-detect residential Windows systems running a Remote Desktop Protocol (RDP) connection exposed to the Internet. This typically involves brute forcing millions of RDP servers all over the world. Facebook and Google continue enforcement action against ad fraud, while ad fraud is increasing in channels, including paid search and paid social, affiliate marketing, and over-the-top (OTT) media services, which are streaming media services offered directly to viewers via the Internet.

Click Fraud Solutions

Into this mix, CHEQ for PPC created its own bit of history. Launched in 2020, it has become the only solution to prevent click fraud across Google, Microsoft ads, Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, Bing, Pinterest, LinkedIn, and Snapchat as advertisers face click fraud attacks on any platform.

Get a demo to find out the levels of click fraud on your digital campaigns with CHEQ for PPC.